A little history

If you’re from the same generation as I am, and were already fascinated by cars when you were a kid, then you do remember this impressive orange coupe sporting the famous three-pointed star that appeared in all magazines throughout the Seventies. That’s indeed what it was designed for: to be a showcase of Mercedes-Benz’ know-how. It fulfilled this role splendidly, along with that of test-bed for what were then high technologies.

The C111 was actually the name of more than a single car, but rather of a series of experimental vehicles. The very first model appeared in Frankfurt in September 1969, though it had been submitted to comprehensive tests since April. Its main goal was to experiment a Wankel rotor engine. A three-rotor type rated at 280 hp, this block was unable to demonstrate sufficient capacities, so a C111/II fitted with a centrally-mounted, 370 hp four-rotor engine followed during the spring of 1970, in Geneva. Performances were now astounding, as the car even recorded a reported 290 kph top speed, an impressive figure at the time. Could the car be produced? It was already fitted with such niceties as air conditioning and plush leather seats, while its gullwing doors were a hint at its prestigious ancestor, the 300 SL, so it is possible that Mercedes-Benz considered the possibilities, though it denied it. At any rate, world politics decided otherwise.

Many an automobile maker was then toying with the idea of fitting Wankel engines to their production cars. They were light, compact, simple thus reliable, and could develop high outputs. Their only problem was their huge appetite for gasoline, a flaw that was inherent to their design and thus that no tweaking of any kind could ever solve. But who cared when oil was so cheap and plentiful? The 1973 crisis suddenly broke out to prove otherwise. Oops. Wankel engines were promptly put away in the kind of storage reserved for “brilliant” ideas that had proved not so good after all, being promised to re-enter the limelight at a time that, in all likelihood, would never come. To be frank, we escaped the worse as Wankel engines were also polluting in proportions that today would make any conventionally-powered gas-guzzler of that carefree era appear eco-friendly. Only three manufacturers, then more advanced in their experiments, put Wankel-powered cars in production: NSU, Mazda and Citroën. This generally ended up with more tears than mirth.

The experimental fibreglass coupe from Mercedes-Benz didn’t disappear, though a completely different approach was needed. After a short eclipse, its Wankel engine was discarded, and replaced by the 3.0-litre five-cylinder diesel block that was in use in several production models, first of all the 240 D 3.0. Economy was the new talk of the town, but Mercedes-Benz wanted to demonstrate that it wasn’t incompatible with performance. Thanks to a turbocharger and an intercooler, the C111/IID could reach a remarkable 190-hp output. In June 1976, the car resurfaced in its newest form on the Nardo track, where it broke sixteen world records over two days and a half. During these tests, the C111/IID also lapped the circuit at 252 kph.

The C111/IID’s successes pushed Mercedes-Benz to develop yet another prototype, the C111/III. Gone were the production-like coupe approach of the previous models, the new car was designed from the ground up for records. In April 1978, the very sleek car was again sent to Nardo, where nine records were broken – no longer records for diesel-powered cars, but absolute ones. Average speeds of more than 300 kph were maintained, though fuel consumption didn’t exceed 16 litres per 100 kilometres. The only problem encountered was the explosion of a tyre at high speed, which damaged the car beyond repair – but fortunately a spare car had been brought, so the run was simply started anew.

A last record tempted Mercedes-Benz. It was unofficial, but highly prestigious. In 1975, a Can-Am car had set the fastest average speed on one circuit lap, at 355.854 kph. A new C111/IV was especially prepared to tackle this last challenge. The Mercedes-Benz team returned to Nardo in 1979. On May 5, project manager Dr. Hans Liebold lapped the track at an astounding 403.978 kph. Besides, the car broke a few more records. Then, time had come for all the C111 to head for the museum.

About the model

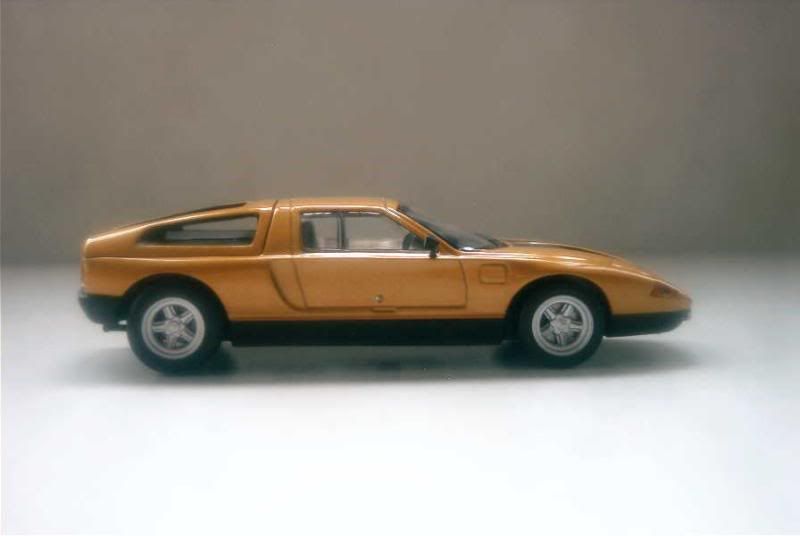

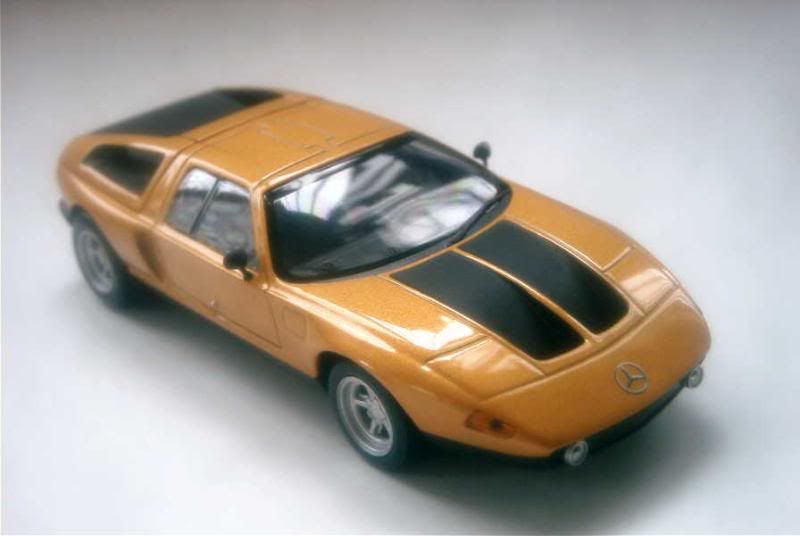

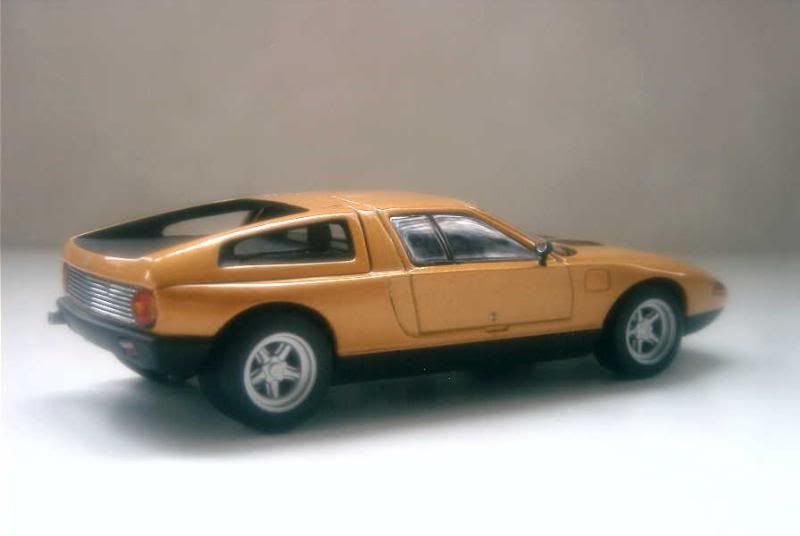

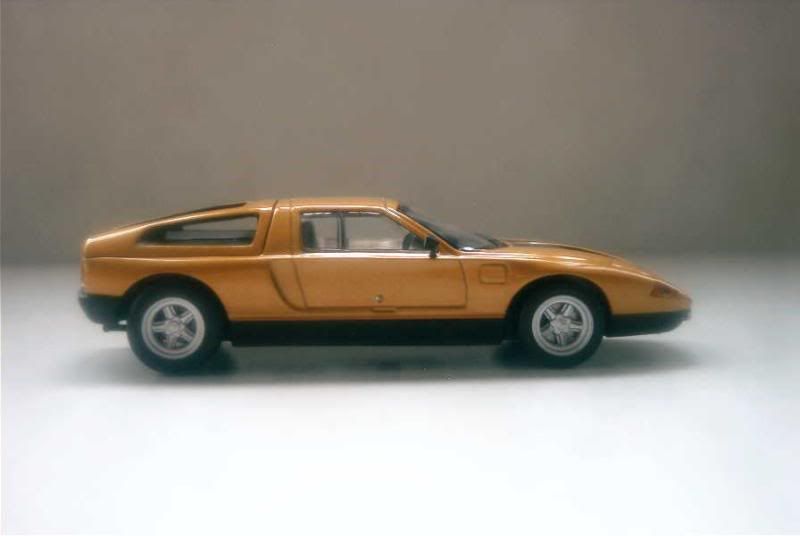

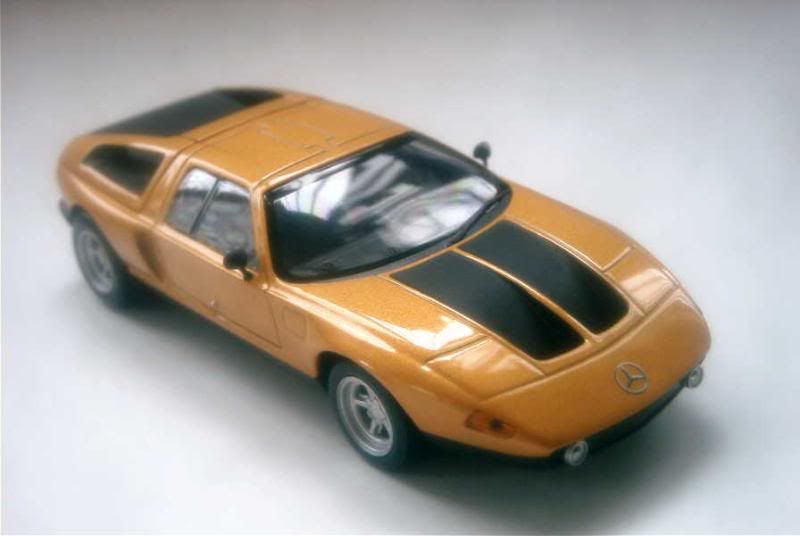

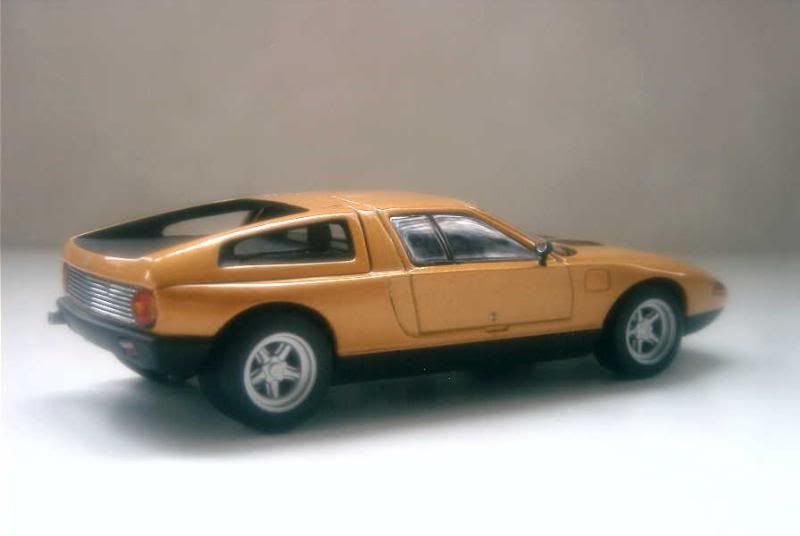

Model: Mercedes-Benz C111/II

Year: 1970

Maker: Minichamps

Scale: 1/43

Distributed by: Minichamps ref. 430-030060, limited edition - 1,440 pieces

Acquired: second hand with box, as a gift from a friend and fellow collector, in August 2010, in Manila, Philippines

That’s a splendid scale model of arguably the most famous of all C111s that Minichamps produces. Though I’m not fond of opening parts for 1/43 models, the German company perfectly adjusted the rear hatch, which discloses the unconventional Wankel engine. All details near perfection, while the model is finished in a superb orange paint, close to the weissherbst of the original. My rating is 17/20.

If you’re from the same generation as I am, and were already fascinated by cars when you were a kid, then you do remember this impressive orange coupe sporting the famous three-pointed star that appeared in all magazines throughout the Seventies. That’s indeed what it was designed for: to be a showcase of Mercedes-Benz’ know-how. It fulfilled this role splendidly, along with that of test-bed for what were then high technologies.

The C111 was actually the name of more than a single car, but rather of a series of experimental vehicles. The very first model appeared in Frankfurt in September 1969, though it had been submitted to comprehensive tests since April. Its main goal was to experiment a Wankel rotor engine. A three-rotor type rated at 280 hp, this block was unable to demonstrate sufficient capacities, so a C111/II fitted with a centrally-mounted, 370 hp four-rotor engine followed during the spring of 1970, in Geneva. Performances were now astounding, as the car even recorded a reported 290 kph top speed, an impressive figure at the time. Could the car be produced? It was already fitted with such niceties as air conditioning and plush leather seats, while its gullwing doors were a hint at its prestigious ancestor, the 300 SL, so it is possible that Mercedes-Benz considered the possibilities, though it denied it. At any rate, world politics decided otherwise.

Many an automobile maker was then toying with the idea of fitting Wankel engines to their production cars. They were light, compact, simple thus reliable, and could develop high outputs. Their only problem was their huge appetite for gasoline, a flaw that was inherent to their design and thus that no tweaking of any kind could ever solve. But who cared when oil was so cheap and plentiful? The 1973 crisis suddenly broke out to prove otherwise. Oops. Wankel engines were promptly put away in the kind of storage reserved for “brilliant” ideas that had proved not so good after all, being promised to re-enter the limelight at a time that, in all likelihood, would never come. To be frank, we escaped the worse as Wankel engines were also polluting in proportions that today would make any conventionally-powered gas-guzzler of that carefree era appear eco-friendly. Only three manufacturers, then more advanced in their experiments, put Wankel-powered cars in production: NSU, Mazda and Citroën. This generally ended up with more tears than mirth.

The experimental fibreglass coupe from Mercedes-Benz didn’t disappear, though a completely different approach was needed. After a short eclipse, its Wankel engine was discarded, and replaced by the 3.0-litre five-cylinder diesel block that was in use in several production models, first of all the 240 D 3.0. Economy was the new talk of the town, but Mercedes-Benz wanted to demonstrate that it wasn’t incompatible with performance. Thanks to a turbocharger and an intercooler, the C111/IID could reach a remarkable 190-hp output. In June 1976, the car resurfaced in its newest form on the Nardo track, where it broke sixteen world records over two days and a half. During these tests, the C111/IID also lapped the circuit at 252 kph.

The C111/IID’s successes pushed Mercedes-Benz to develop yet another prototype, the C111/III. Gone were the production-like coupe approach of the previous models, the new car was designed from the ground up for records. In April 1978, the very sleek car was again sent to Nardo, where nine records were broken – no longer records for diesel-powered cars, but absolute ones. Average speeds of more than 300 kph were maintained, though fuel consumption didn’t exceed 16 litres per 100 kilometres. The only problem encountered was the explosion of a tyre at high speed, which damaged the car beyond repair – but fortunately a spare car had been brought, so the run was simply started anew.

A last record tempted Mercedes-Benz. It was unofficial, but highly prestigious. In 1975, a Can-Am car had set the fastest average speed on one circuit lap, at 355.854 kph. A new C111/IV was especially prepared to tackle this last challenge. The Mercedes-Benz team returned to Nardo in 1979. On May 5, project manager Dr. Hans Liebold lapped the track at an astounding 403.978 kph. Besides, the car broke a few more records. Then, time had come for all the C111 to head for the museum.

About the model

Model: Mercedes-Benz C111/II

Year: 1970

Maker: Minichamps

Scale: 1/43

Distributed by: Minichamps ref. 430-030060, limited edition - 1,440 pieces

Acquired: second hand with box, as a gift from a friend and fellow collector, in August 2010, in Manila, Philippines

That’s a splendid scale model of arguably the most famous of all C111s that Minichamps produces. Though I’m not fond of opening parts for 1/43 models, the German company perfectly adjusted the rear hatch, which discloses the unconventional Wankel engine. All details near perfection, while the model is finished in a superb orange paint, close to the weissherbst of the original. My rating is 17/20.